From Paris With Love

Treize, Paris

7th November - 17th December 2022

Toulouse Lautrec's late nineteenth century paintings are synonymous with Paris's cultural image, so much so that over a century later they still generate a nostalgic desirability for the French capital.

These paintings' popularity is so vast, that for a majority of people who see them in tourist shops, on products such as postcards or magnets they resemble nothing more than a hazy mirage of Paris's ‘heyday', a time of opulence and decadence, a time without responsibility and an image without specific context other than emitting a particular mood. We are made to understand that they have been made by a great man who had a great time.

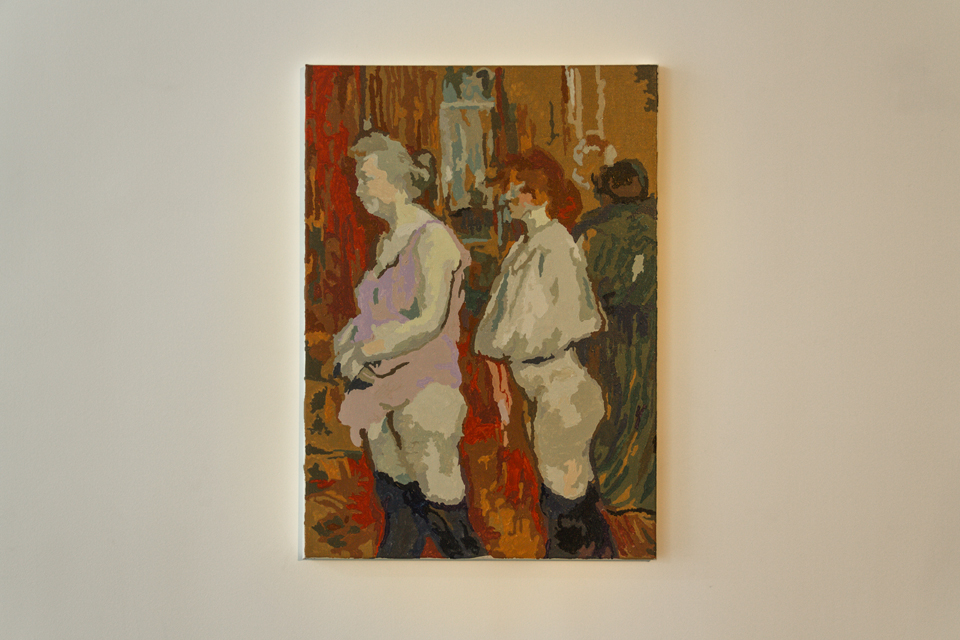

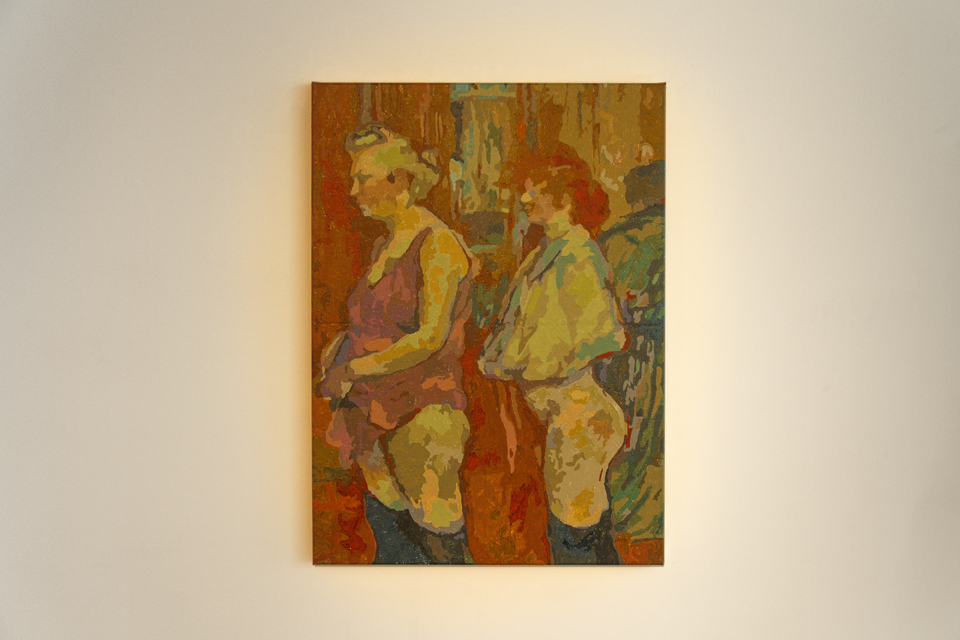

The Medical Examination, 1894 or sometimes called The Medical Inspection 1894 is an oil painting by Toulouse Lautrec. It shows a side profile view of two women in a red room. These women are not facing the painter and they seem to be queueing or waiting. Their chemises are turned up, revealing their naked butttocks and thighs, their stockings pushed down. Their breasts are covered. This state of being semi dressed where the genitals are exposed but not the breasts is an utterly uncommon female position.

These women are sex workers and this painting shows them at work. They are waiting for a medical inspection in a Parisian brothel that the painter frequented. In 1810 in France it was made mandatory for prostitutes to have medical examinations for venereal diseases every eight to fourteen days by two doctors and one police man, all of whom, unsurprisingly were men. If their results were positive, they would be sent to prison. Waiting is synonymous with sex work.

The painting shows a particularly unsavoury delight and satisfaction in finding the female both body grotesque and alluring. The sex worker is the main target for the abject contradictions of desire and disgust that the feminine body so often contains, having to inhabit both extremes which the patriarchal gaze is so fixated with.

Toulouse Lautrec's oeuvre has been highly commodified through Paris's tourism industry and with this comes a diluted, if not entirely polluted, superficial consumption of the artist's work. He is perhaps best known for his poster design for the Moulin Rouge, a place that still to this day brings in a fortune to the French capital's economy. It is because of how his legacy has been deployed that this particular painting can seem almost innocuous, a throw away comment amidst this male artist's ability to capture moments of him enjoying himself with paint and canvas and by in turn inviting the viewer to enjoy themselves too.

This bind was accelerated in 2001 upon the release of Baz Lurhmann's Hollywood movie of the same name, a camp extravaganza mythologising this period of time, taking largely from Emile Zola's novel Nana (1880), glamourising this bohemian period and even including a character based on Toulouse Lautrec. This film diverted any attention from its inherent dependence on sex work and instead intoxicated the viewer with a bathos infused narrative about romance and more odiously- the man ‘saving' the sex worker from the depths of his apparently pure hear, rendering Nicole Kidman's character a helpless victim.

At the turn of the century, syphilis was considered the destroyer of the bourgeois status quo and it was the sex workers who were punished for this outbreak. The sex worker is and will always be one of the most potent political identities and this will never change because she always has the potential for the upheaval of any existing social power structure because she caters to the invisible behaviour of the respected.

The Medical Examination, 1894 exemplifies the friction between its period's desire for decadence and the banality that modernist capitalism began to enforce on its workers. It shows the work behind the ‘scenes', the sex worker when she is not ‘on show' and how labour is often out of control for the worker.

Of course this is an artwork about humiliation but it is also about boredom, anxiety and labour. I want to contrast this with how this painting is instrumentalised in the contemporary practices of leisure, especially that of tourists visiting Paris who are usually unconsciously unaware of their own investment with sex work and instead revel in the superficiality of how this period of Paris's art history is presented and consumed.

Toulouse Lautrec was and is widely championed for showing a more ‘human' side of these workers. It should not be the artist who is championed for this but the women. Old women are usually forgotten women. Nostalgia is a disease and this painting is sick.

Paint by number kits were invented in America in the 1950s, a sort of post war invention that boomed throughout North America and gave the consumer ‘the experience of art without being an artist.' The paint by number kit gives the activity of leisure, perhaps even a hobby, which is something many men consider themselves to be doing when they visit sex workers. It is also something that tourism fulfils, existence momentarily in a space you do not truly inhabit. Intimacy without intimacy, and/ or an experience without commitment to a culture.

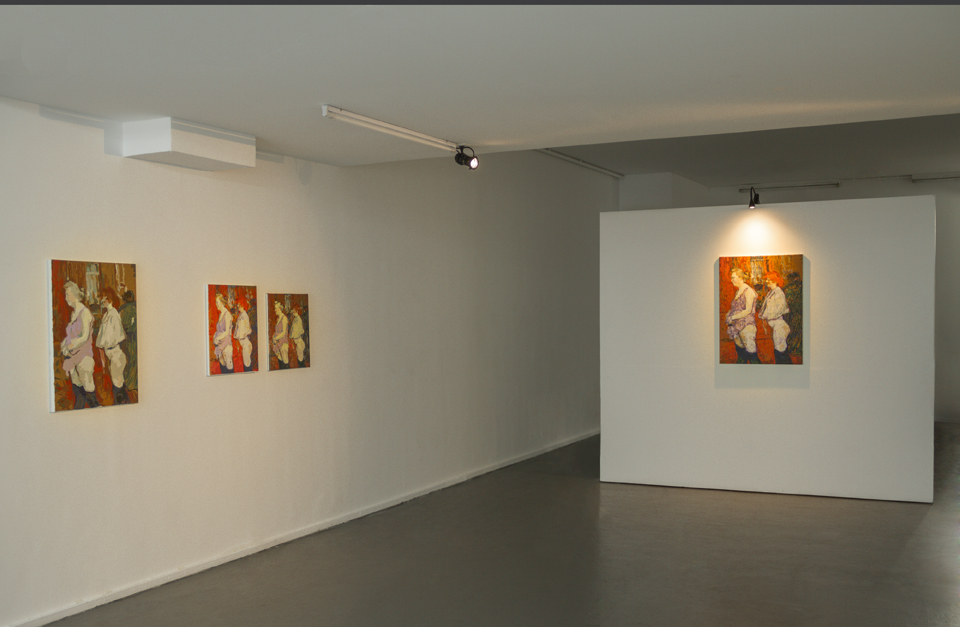

I am having my submissives recreate this painting by using paint by number kits. Eight were started and six were completed by My submissives in three different countries. The usernames of active john's looking for sex workers in Paris have been printed onto souvenirs and will be able to be bought at this exhibition. These usernames have been drawn by My submissives in the style of famous male artists signatures. The unsellable man can and will be fucked into sentimentality. All profits from the sales of the john's merchanise will go back to a sex worker activist group working in Paris today, STRASS - Syndicat du TRAvail Sexuel. I like to laugh at imagining the john turned into a pathetic, nice souvenir object and I hope you will too.

Reba Maybury, Paris, November 2022.

Curated by Juliette Desorgues with collaboration from Olga Rozenblum

Supported by Fluxus Art Projects

Install photographs by Lheo De Sosa